Rocklin’s Chinese-American Legacy

How Chinese Americans Built California and the History of Violence They Encountered

The City of Rocklin is a strong community with many accomplishments we are proud of. But as we anticipate our bright future, it’s important to reflect on our past as well, and the place our City had in the history of California and its diverse population.

The Forgotten Rocklin Chinatown

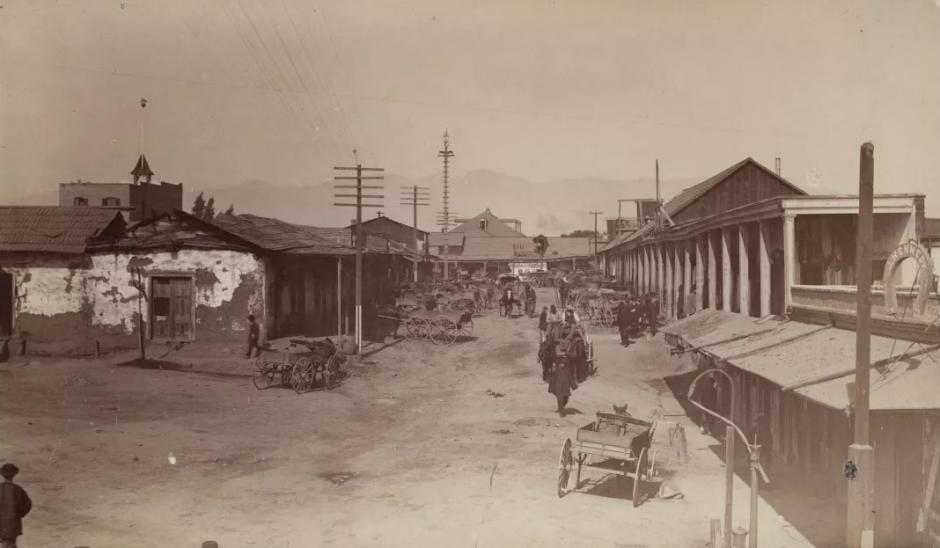

Today Chinatowns in San Francisco and Los Angeles are world-famous tourist hotspots, featuring distinct Asian cuisine and events. Chinese immigration to the United States was widespread in California in the 1860s, and nearly every city in Placer County, including Rocklin, hosted growing communities of Chinese immigrants. Yet today, the only remnants of these once thriving Chinese American neighborhoods are a few buildings and the occasional historical marker.

Chinese Come to California

Local Chinatowns were formed during a wave of Chinese immigration to California after the Gold Rush. Over 2.5 million Chinese individuals fled their home in the 1850s and 1860s as a result of the devastating Taiping Rebellion that took an estimated 20 million lives in China. Like most immigrants to the United States, Chinese immigrants sought stable work, safety and security, and a means of support for their families in a new country.

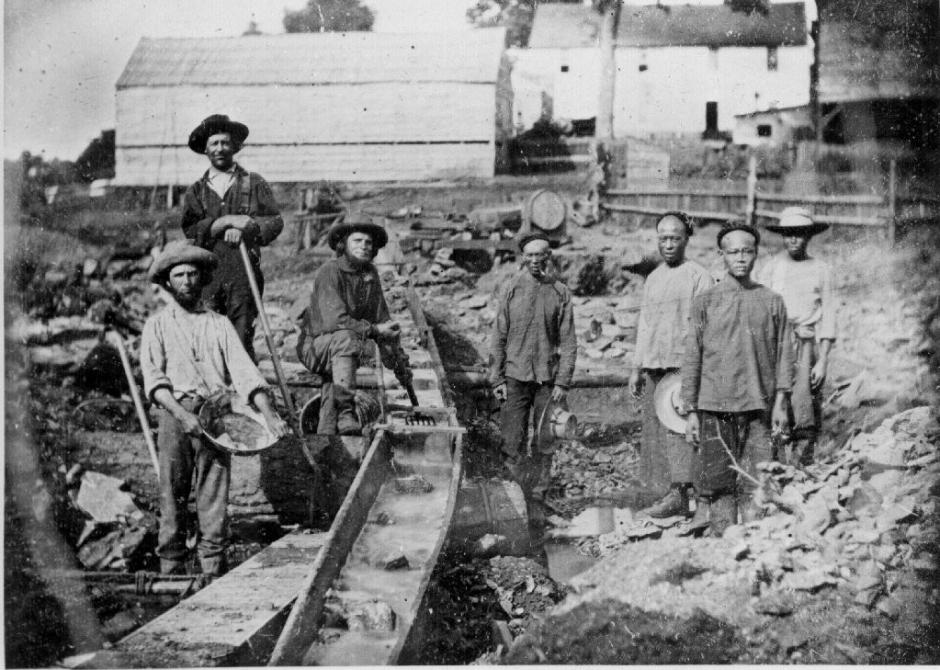

Chinese immigrants found work in mining, agriculture, forestry, and the building of the Transcontinental Railroad. In new frontier communities, they operated general stores, restaurants, and laundries. Their contributions to the economy and wealth of the Golden State should not be underestimated, but they are often forgotten in the retelling of the history of the West.

How Chinese Immigrants Built the Transcontinental Railroad

From 1863 to 1869, roughly 15,000-20,000 Chinese immigrants worked to build the nation’s first Transcontinental Railroad. The job was back-breaking, dangerous, and unforgiving. Freezing winters, scorching summers, accidental explosions, landslides, and disease killed many workers as they laid miles of tracks a day, built roadbeds, and drilled dynamite into sheer cliffs.

Initially, the Central Pacific Railroad was reluctant to hire Chinese immigrants. But labor shortages and the tight timeframe of the project pressured Central Pacific Railroad Director, Charles Crocker, to hire Chinese workers when only a few hundred white laborers responded to ads for the jobs available.

By 1867, 90% of railroad workers were Chinese. Leland Stanford, founder of Stanford University, former California Governor, and President of the Central Pacific Railroad, told Congress in 1865 that the contribution of the Chinese was irreplaceable (qtd. from The Industrial Revolution in America by Kevin Hillstrom):

Without them, it would be impossible to complete the western portion of this great national enterprise, within the time required by the Acts of Congress.

Despite the contribution of Chinese laborers, they were poorly treated and unfairly paid. Stanford University Professor Gordon Chang (author of Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad) points out that, “Chinese received 30-50% lower wages than whites for the same job and they had to pay for their own food stuffs.” While the railroad company provided its white laborers room and board in train cars, Chinese workers had to support themselves and live in tents outside.

Chinese American Contribution to California’s Agricultural Wealth

In addition to the railroad, Chinese labor significantly contributed to the wealth of the Central Valley by way of agriculture. The land that was once free and home to many California Native American tribes, including the Nisenan, Miwok, and Maidu (who lived in land that today includes Rocklin and Roseville), was sold in large tracts to elite, wealthy land owners.

University of Delaware professor Jean Pfaelzer and author of Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans credits the work of these Chinese Americans to the economic success of agricultural California:

The Chinese would build the infrastructure of a new county, dynamiting roads, clearing fields, digging ditches to supply water to the mines, and constructing hundreds of miles of stone fences.

In Rocklin, Joel Parker Whitney, purchased 18,000 acres of land in the 1860s and 1870s and became one of Placer County’s wealthiest people. Whitney hired approximately 1,000 Chinese laborers to do the work of road building, bridge building, fruit cultivation, and construction on the land.

Despite the importance of Chinese work to the wealth accumulated by California’s growing land-owning class, they were consistently the victim of discriminatory laws and practices and an increasing amount of racist violence from their non-Chinese neighbors, and were paid a fraction of the pay of white workers.

As the 1800s wore on, the gold mines that drew many settlers and immigrants to California began to dry up and jobs in the railroad and agriculture became increasingly scarce. A depression in the 1870s swept the country and bankrupted the largest bank in the nation at the time, Jay Cooke and Company. The difficult jobs on orchards and lumbermills suddenly became lucrative––the same jobs often occupied by Chinese immigrants.

In Los Angeles in 1871, violence broke out against Chinese, sparking a wave of hate that would spread all the way to the small growing towns of Rocklin, Roseville, and Loomis.

California Takes a Dark Turn

California’s Chinese population was instrumental to much of what made California successful, but constantly faced discrimination and prejudice. In the 1870s, these Anti-Chinese feelings would escalate into a wave of violence across the state, leading to the destruction of Rocklin’s Chinatown.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1854 became first federal law that restricted immigration based on nationality. Across California, the Chinese population were denied interracial marriage and integrated schools. Despite these discriminatory laws, Chinese protested in the streets and filed over 7,000 lawsuits in defense of their lives and dignity.

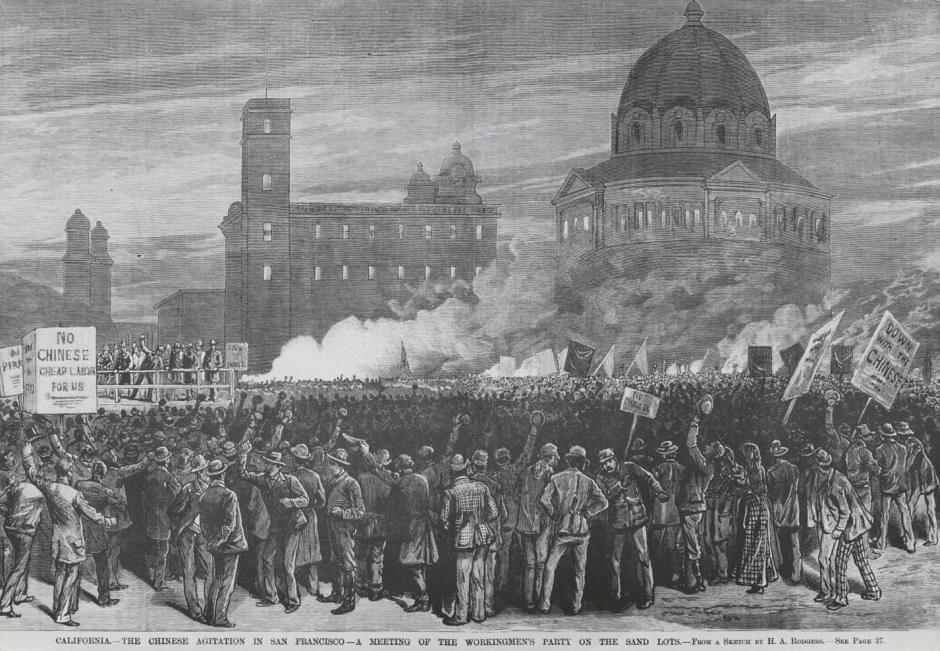

The depression of the 1870s was the spark that flamed existing Anti-Chinese sentiment into overt demands to drive out the Chinese. The low-paying jobs on orchards and ranches and doing laundry or providing childcare were often done by Chinese immigrants. But in the growing hard times, even these jobs were lucrative. Soon, numerous labor organizations, including San Francisco’s Workingmen’s Party of California and Sacramento’s Supreme Order of the Caucasians, sprang up to force Chinese workers from their jobs and livelihoods.

The Los Angeles Chinese Massacre (October 1871)

The first major act of violence was one of the largest mass lynchings in California, in El Pueblo of old Los Angeles. Nineteen Chinese were murdered after 500 men stormed the Chinatown and shot and hung those who tried to escape. The few individuals brought to trial for the Chinese Massacre of 1871 were, within a few months, all released.

Lemm Ranch Murders (March 1877) and San Francisco Riots (July 1877)

This type of violence continued across California. In Butte County, an Anti-Chinese labor group attacked and killed six Chinese workers at Lemm Ranch in Chico on March 14, 1877. The next day, the local Chinatown was burned. Threats were sent to the businesses and ranches in the area, demanding they fire all Chinese workers. Meanwhile, in July of the same year in San Francisco, 6,000 men marched to burn down the docks of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, the largest carrier of Chinese immigrants. Mass looting and assaults followed in Chinatown, leading Chinese merchants later to sue the city for over $100,000 in property damages. This riot launched the Workingmen’s Party of California, a group that was elected to the State Senate and State Assembly and attempted to rewrite the California constitution to deny the vote to Chinese citizens and to outlaw any employment of Chinese individuals.

Rocklin Drives Out Chinese Residents (September 1877)

Up until 1877, the residents of the small Chinatown in Rocklin (located behind the Rocklin Roundhouse) lived in relative peace alongside Rocklin’s other citizens. A small railroad town, Rocklin was home to the Chinese who worked on the Central Pacific Railroad for the previous eight years. They also worked for nearby ranches doing hand laundry and growing vegetable farms in the flatlands just outside old Rocklin, at today’s China Garden Road. Rocklin was home to 400 Chinese people compared to a white population of 542, consisting mostly of Finnish and Irish immigrants (according to the 1870 census).

The trouble started on September 15, 1877, when three white individuals were attacked at a ranch in Secret Ravine, including ranch owner H.N. Sargent. All three died, but before his death Sargent said that the men who attacked him and killed the other two on his ranch were Chinese men who had visited his ranch recently to purchase a mining claim.

Police from Rocklin and Roseville found ten Chinese men about 150 yards from the scene of the crime and arrested them. Outside the jail, an angry mob began to form, threatening to hang the accused.

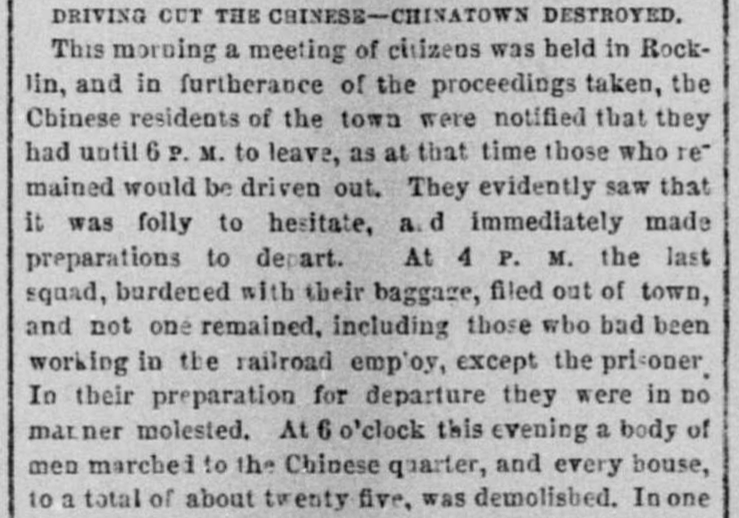

Before the police could collect any evidence on the crimes, the mob demanded that all Chinese residents leave the town by 6 p.m. of September 16: “Those that remained would be driven out,” they declared. With the recent memory of mass lynchings and rampant destruction across the state, the Chinese in Rocklin packed up their belongings and left the town. In their wake, the mob demolished the small Chinatown, and soon every shop and house was in flames.

When the police finally declared that there was no “sure and conclusive” evidence against the Chinese suspects, an angry crowd gathered outside the prison. Fearing the mob, the Rocklin sheriff boarded his prisoners on a train out of town. While they waited for the train to leave for Auburn, the mob rushed the railroad cars, demanding to lynch the Chinese prisoners. Rocklin police officers and the train conductor managed to throw off the men and leave Rocklin safely. In the end, the Sargent ranch murderers were never caught.

These actions were an instant touchstone for similar expulsions in the local area. The next day, Penryn ordered its Chinese out, and Roseville demanded the Chinese leave the following day. On September 17, ten armed men rode through the Chinese camps along Auburn Road and threatened sixty Chinese miners to leave “under penalty of death.” That night, one hundred armed men searched the forests for any Chinese who did not hear the ultimatum. Soon, Loomis too purged its Chinese. A few days later, Chinatowns in Grass Valley, Walnut Grove, and Dutch Flat were torched. Foothill towns canceled Chinese leases, and Gold Run mine owners fired their Chinese employees.

Chinese refugees fled across the Sierra foothills and the Sacramento Delta and settled in a camp in Folsom, but were soon discovered by armed men on September 21 who shot into the tents and shelters and threatened to drown anyone who tried to escape.

Despite the intense violence, some Chinese still remained in Placer County. By 1880, 13% of the county population was Chinese. But the Chinese never returned to Rocklin. In 1879, those who lived in Rocklin claimed that the Chinese could not be employed or rent a home in Rocklin.

The Chinese in Rocklin had owned land and mining claims for several miles around the town, and in the wake of the destruction, they declared that they would seek reparations through the law for the loss of their property. Their case also came to the attention of New York attorney Frederick Bee, one of the nation’s first opponents of Anti-Chinese sentiments in the country. In 1877, Bee filed a suit against Placer County on behalf of every Chinese resident who was expelled from their homes and lost their businesses and property. He demanded the Rocklin sheriff arrest over twenty rioters who had been identified by the Chinese. But no arrests were made, and area newspapers and Governor Irwin soon accused Bee of exaggerating the violence and turning national sentiment against California and its Anti-Chinese actions.

California Today

The 1870s were a dark time in the history of Chinese residents in California, when economic fear and racism bred violence across the state. Despite the ugliness in these histories, it is important to recognize that these are also the events that shaped our town and state and inform our future.

Today, California is home to over 6 million Asian Americans, including over 1.5 million Chinese Americans. In 2019, California celebrated its first Chinese American Day on October 23, the first official recognition of Chinese Americans by a state legislature. Today, the City of Rocklin is home to over 70,000 people, 11% of whom are Asian American.

C.C. Yin, founder of the Asian Pacific Islander American Public Affairs Association (APAPA), said on the day of California’s first Chinese American Day, regarding the importance of celebrating the contribution of Chinese Americans in our country:

This is important not for Chinese Americans only, but for all Americans because America was founded under the principle of liberty and justice. From here on, what do we do? That’s really important what to say about why today’s important. It’s about tomorrow, it’s about the young generation… It’s to make America a better country.

For more resources on Chinese American history in California and Rocklin, visit the Rocklin Historical Society, read Joel Parker Whitney’s memoir Reminiscences of a Sportsman, or check out Jean Pfaelzer’s Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans at the Rocklin Library.